The factors behind exclusion from secondary are multiple, diverse and intersectional

Out-of-school adolescents are disproportionally in fragile countries, countries affected by conflict, or climate crisis. They face multiple challenges, including financial constraints, a lack of access to schools, harmful social norms, poor quality provision of education and limited opportunities for work. Disabilities are significant barriers to secondary education.

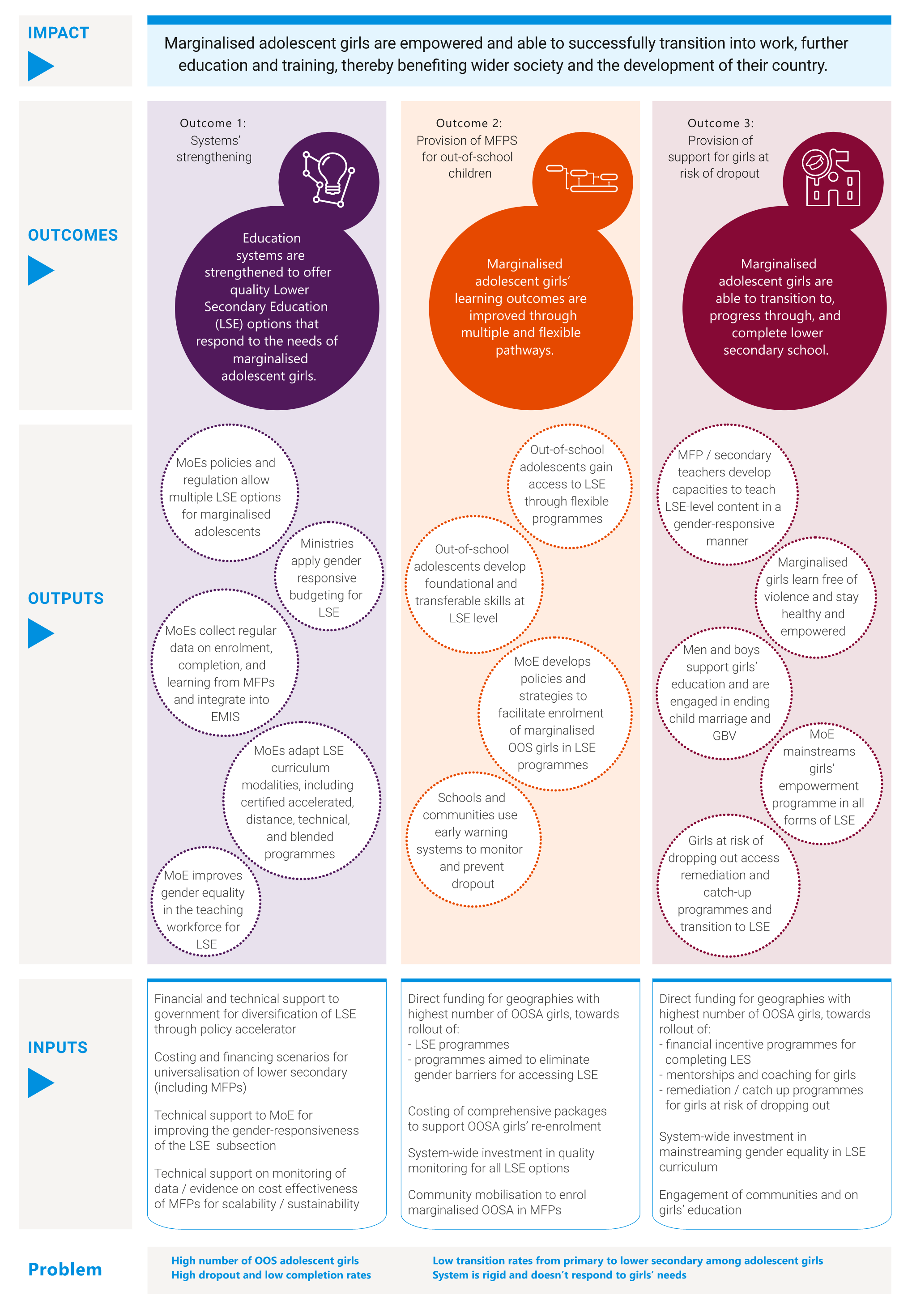

In many places adolescent girls are particularly disadvantaged, with a range of gender norms and gendered barriers – including child marriage, expectation of fulfilling household duties, or expulsion due to pregnancy – leading to an early end of education every year. Even when girls progress to secondary, these norms can mean lower entry rates into further education and/or the labour force inhibiting their potential. A lack of safety in and around schools also leads to lower attendance and higher dropout rates for girls at higher levels.

Poverty, social exclusion and gender norms, including harmful masculinities, also impacting boys’ access to education; many drop-out early to join the labour force, but into low-skilled occupations and in poor conditions. This requires urgent policy attention and a gender transformative design of education, enabling girls, boys and gender diverse children to succeed.

Each context and challenge require different solutions; adolescents in poverty simply cannot afford fees or the other indirect costs of education and many need to work to make ends meet. Work is mostly incompatible with school timetables, increasing absenteeism and the risk of dropping out. Those living in remote and rural areas walk miles to often overcrowded schools. Given the need for specialist teachers, many countries can’t afford to provide traditional schools within walking distance. For these children, community-based education can be a lifeline.

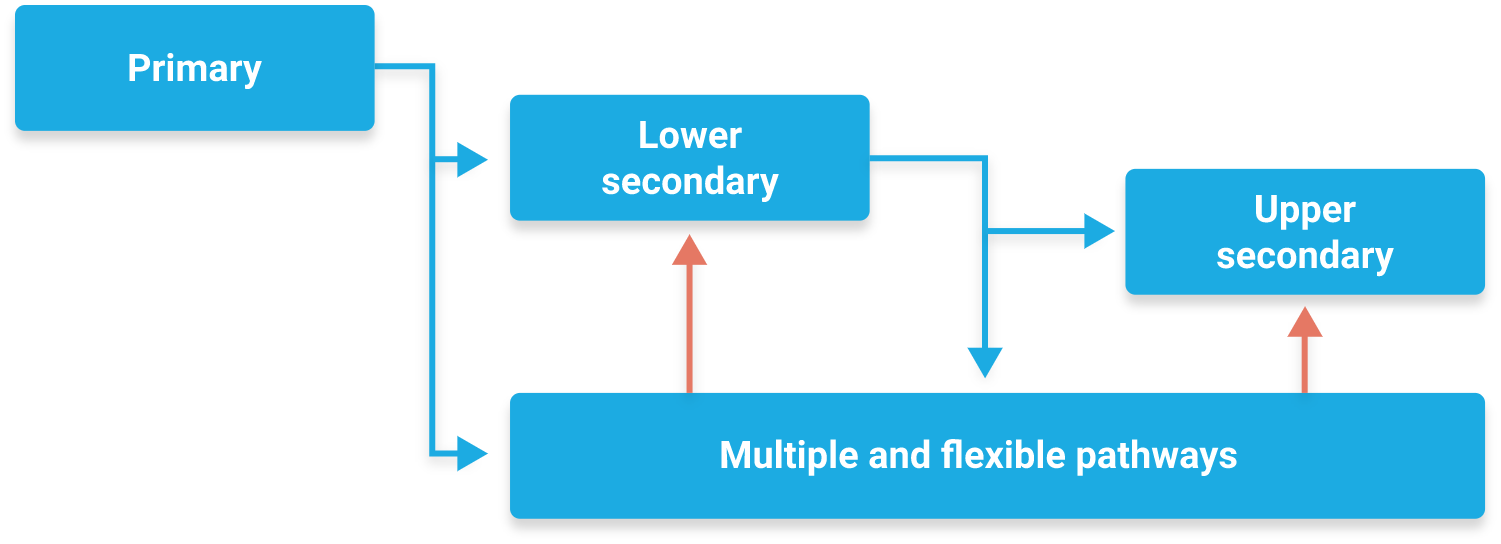

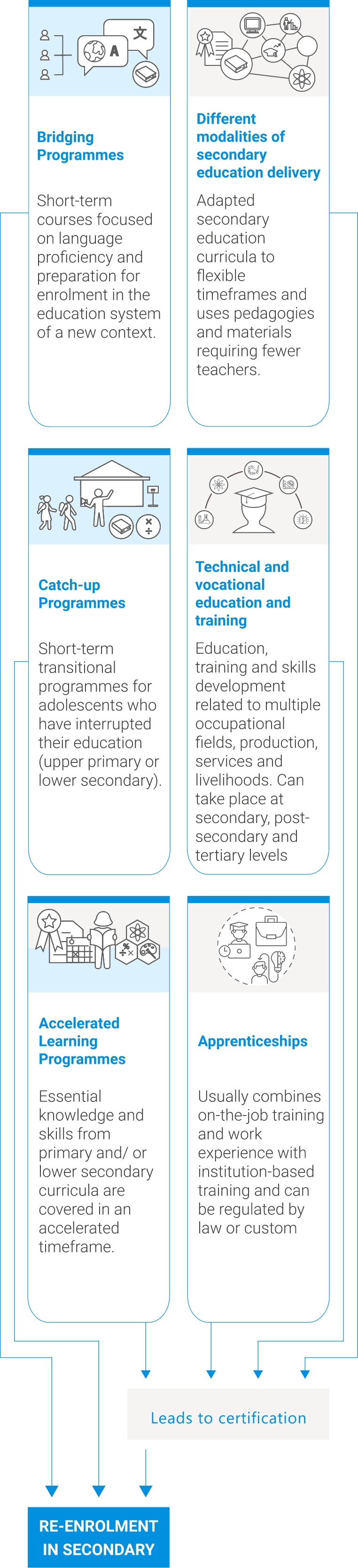

Many children are discouraged by low quality education and narrowly focused curricula that was designed to prepare them for tertiary education in specific professional fields. An academic path that lacks relevance for their different life paths and that doesn’t encourage the development of critical transferable and labour market skills is causing millions of adolescents to disengage from education. Maintaining learners’ interest and addressing disengagement and drop out requires diverse learning options beyond the linear academic pathway.

Many projects have tried to solve these issues and have been successful on a small scale (see selected case studies below). However, solving them at scale means taking bold steps to reimagine secondary education as a system that includes many pathways; pathways that provide relevant knowledge and skills and are available for all children and adolescents – to keep those in school from dropping out, and to get those who have dropped out back in and to stay in.

Read More

Read More